Building portfolios of limited partnership funds

Assuming we want to design and manage portfolios of illiquid limited partnership funds by taking their cash-flow characteristics and Environmental, Social & Governance factors into consideration, the following sections identify some challenges faced by LP investors.

Satisfying ESG objectives

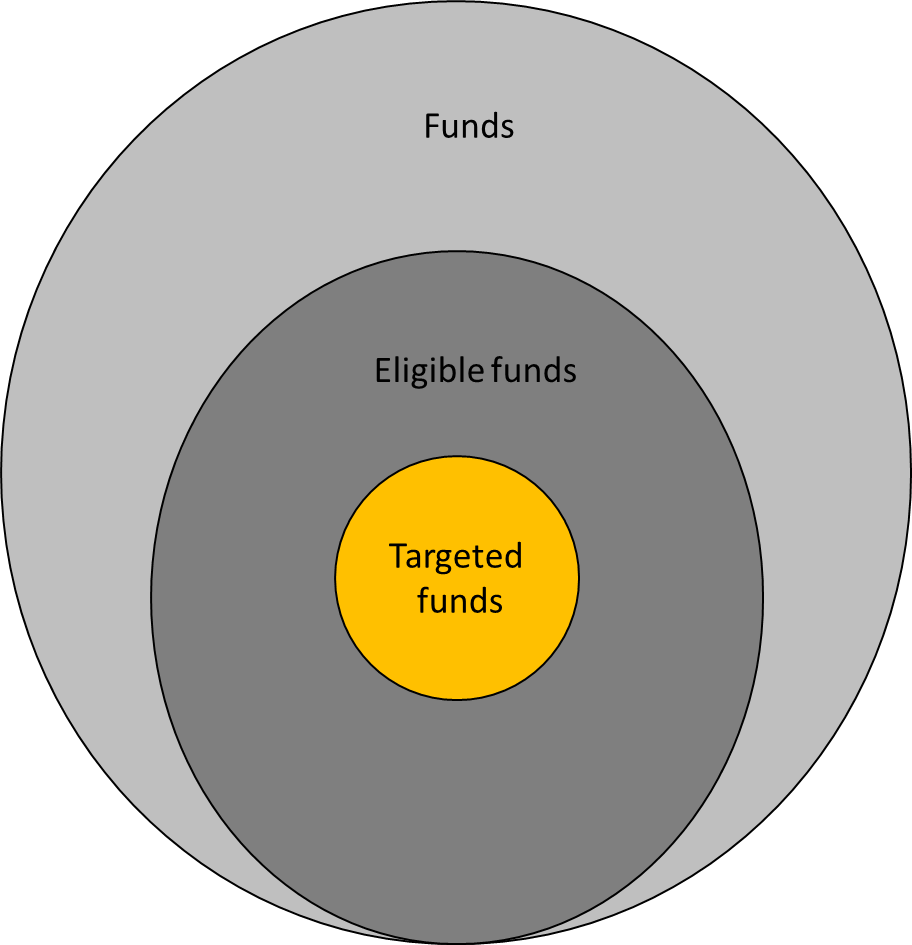

Hereafter, we suppose that LP investors have already filtered non-eligible funds, i.e., funds which do not meet the minimum requirements according to their own ESG objectives. Among the set of eligible funds, a subset represents promising ESG-compliant funds targeted by LP investors in priority. LP investors have to cope with an additional decision problem consisting in maximizing the recommitments into the targeted/preferred funds while aiming to maintain stable the global exposure to private equity.

Treatment of uncalled capital

Generally, the true exposure to private equity is viewed as the capital that is actually invested (see Oberli, 2015). This is debatable as the LP’s liquidity risk is the highest at the time of the commitment and during the fund’s early years when the bulk of the capital is yet to be called but its investment level has not reached its peak. Investors need to draft a commitment-pacing strategy, i.e. on how to size and time their commitments in order to achieve and maintain the targeted allocation to private equity while respecting the liquidity constraints imposed by the uncalled capital.

Commitment Pacing

So far portfolio model based on cash-flows tend to be over-simplistic and usually focus on commitment-pacing, i.e. on how to size and time their commitments in order to achieve and maintain the targeted allocation to private equity while respecting the liquidity constraints imposed by the uncalled capital. Usually these models are spreadsheet-based, very simple and work through ‘trial-and-error’. The impact of (alleged) skills when selecting high-quality funds is either not reflected or over-estimated. Often for the targeted portfolio composition there are no funds with desired characteristics available or not available at the time. Also, the interaction with the secondary market for funds is difficult to factor in, as they tend to try up precisely when LP experience liquidity problems.

Over-commitments

The costs of maintaining the uncalled capital as dry powder is a widely overlooked expense of investing in private equity (see Arnold, 2017) and still ignored by academic research (see Meyer, 2020). In practice, LPs therefore run so-called over-commitment strategies, i.e. committing more capital in aggregate than actually available as dedicated resources, with the gap expected to be filled by future distributions from the existing portfolio of funds. Over-commitments share important commonalities with leverage strategies and show similar rewards and risks, notably that of becoming a defaulting investor and incurring significant financial and reputational penalties.

Recommitment strategy

Achieving and maintaining high allocation to private equity and keeping allocations at the targeted level is a complex task and needs to be balanced against the risk of becoming a defaulting investor. According to de Zwart (2012), this issue has received very little attention in the literature despite the fact that the costs of inefficiently (re)committing can be significant. These authors propose a recommitment strategy for funds aiming to maintain the exposure to private equity stable. The strategy’s key feature is that the level of new commitments in a given period depends on the current portfolio’s characteristics. Importantly, it does not take cash-flow forecasts for the funds into account.